Being a dad ain't what it used to be. Women have more choices than they did prior to the feminist movement, and that means men also have more choices. My name is Jeremy. I'm a writer and publishing consultant, but mostly, I take care of my 19-month-old son Liko. It started in July, when I quit the job that I hated and started a freelancing career. Friends had suggested that I should write about being a mostly stay-at-home dad. Until last week, I always said, No, I’m not going to write about being a dad; not yet, anyway.

Being a dad ain't what it used to be. Women have more choices than they did prior to the feminist movement, and that means men also have more choices. My name is Jeremy. I'm a writer and publishing consultant, but mostly, I take care of my 19-month-old son Liko. It started in July, when I quit the job that I hated and started a freelancing career. Friends had suggested that I should write about being a mostly stay-at-home dad. Until last week, I always said, No, I’m not going to write about being a dad; not yet, anyway.

But recently I surprised myself by posting a blog entry to Other Magazine about it, and I realized that I was ready to start writing and thinking about fatherhood, and maybe help other dads in the process. This is what I wrote, which I'm sharing as the first entry in my new blog:Here’s the thing: I don’t think I deserve a medal and I don’t think every dad should do what I’m doing. Not everyone can. We’re lucky – it’s all relative – that my wife’s job has solid benefits and that I can still make enough money as a freelancer to pay our $1,800 rent (in San Francisco $1,800 gets you a one-and-a-half bedroom apartment with a deck). Yes, I read newspapers and I’m aware that I’m supposedly part of a trend. “The number of stay-at-home dads almost doubled from 1994 to 2004 – from 76,000 to 147,000 – according to the U.S. Census,” says a Feb. 22

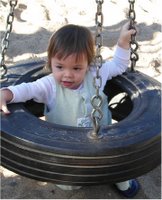

article in the Contra Costa Times. But let’s put that in perspective: 147,000 is nothing compared to the millions – billions, if you look worldwide – of women who defer careers, hobbies, adventures, and sex lives to take care of a legion of children. Even in liberal, genderfucking San Francisco, I’m still usually the only dad in Liko’s music and swim classes, and usually the only one of the playground before 5 pm. Yes, I quit my job and powered down my so-called career so that I could take care of my son. I did it because I wanted to, not to be somebody’s role model.

And you know what? – I’m addressing you gentlemen, in particular: I’ve given up a lot, many things besides just a job. I don’t write stories and

poems and

essays like I used to; I no longer organize readings and fundraisers; my social circle has shrunk significantly. I don’t go to movies. I usually rise at around 5 am – I work in the mornings, and I make enough money as a freelancer to have my own office – and sometimes, when it’s still dark and I’m standing in line for coffee, I can feel my old life twitching like a phantom limb. I want to jump out of line and go running back to 2003, when I could just decide that today, I’m going to sit in a café and read, and then later, I’m going to see a movie, and then after that, I’ll go to the

Make-Out Room and get drunk with my friends. Today in 2006 I’m just tired all the time. When I have a free moment, I do the dishes.

Does anything I just wrote mean that parenthood and staying home with Liko is a drag? Do I feel sorry for myself? Fuck no. I’m not a good enough writer to tell you how holding him makes me feel; let’s just say it feels good. When we’re blasting Yo La Tengo or the Strokes or Blondie (his favorites; he has a thing for punk, new wave, indie pop, etc.; anything that bounces, really) and I’m dancing and he’s careening down the hall, arms flailing, hopping from one foot to the other, and then he runs up and hugs my leg and yells “Dada!” – life can’t get any better. Nobody gives a shit about my poems anyway; the world can live without my stories. Most movies suck. From where I stand in 2006, the Jeremy of 2003 looks like an emotionally parsimonious, spiritually puerile wanker. I helped make a new life, and that’s staggering: a new human being, and a new life for me. I don’t want to give him to a nanny; I want to take care of him and see him grow. I wish I were with him now. Writing this, I feel like I’m stealing time from him.

It’s probably impossible – and there’s no shame in this – for a non-parent to understand the Heaven and Hell of being a parent. It’s a whole cosmos unto itself, ruled by Satan on one side and Jehovah on the other, and you never quite feel whole – or at least, I don’t. There are two of me now, one who yearns for freedom and the other who wants nothing more than to be chained to my drooling, pooping, cuddly little boy. I’m still new at this, still in the process of being transformed in ways both bad and good; maybe in time I’ll grow up and the two sides will merge into a whole person. More likely, judging from the patterns I’ve seen in my family and in older parents, it’ll be a seesaw, with one side and then the other getting heavier, lighter, heavier, wishing, accepting, wishing. And when he’s gone and can take care of himself, who will I be? Well, I’ll let you know when I get there. Humans have been raising kids and facing life cycles since we came down from the trees, but I’ve got a lot more going for me than my flea-bitten, ant-eating ancestors on the African savannah. I’ve had more choices than most people have in the world – certainly more choices than most women have ever had.

Where was I? Right: I’m supposed to be a trend, according to the Contra Costa Times. Well, it’s a pretty small fucking trend and I guess that I’m not interested in making it any bigger – or maybe I should say, I don’t feel I have the authority to tell anyone how they should structure their family life. I just want to get through to the end of the day. Parenting is brutally hard and wonderful work and it’s not for everybody; most men in our society will resist making the sacrifices involved with staying home – and why shouldn’t they resist, really? What’s in it for them? To be seen as a heroic pioneer? Fuck that. Why, for that matter, should moms be pushed into working so that the guy can stay home? Moms are never interviewed in these trend stories – how do they feel about it? (Maybe that’s the story I should write.) Why, now that I think about it, should anybody be forced to work a 50-hour week at a job they hate? Dads-at-home will be a tiny minority for as long as parents have to scramble to keep their heads above water, trying to make enough money to survive and give their kids the best life possible, under the circumstances. If Americans – we fat, rich, selfish, sadistic, TV-watching bastards – really wanted to encourage stable families and more paternal responsibility in raising kids, we’d raise our boys to be caregivers, guarantee health care for everyone, build more affordable housing, and require and incentivize employers to give all new parents, poor and middle-class, a break. Until all that happens, don’t talk to me about trends.

--------------

Since I published that entry, I’ve heard from quite a few people (in other blogs, through email, and on the Other forum) and they’ve made me conscious of its impact. When I wrote what I wrote, I made a deliberate decision to shut off my rational, responsible filter and just say what I felt. After I published it, I realized (everybody but me will have seen this) that the very act of describing my experience in a public forum made me an example, and that example could encourage (or discourage!) other dads to consider, circumstances permitting, taking on more childcare and even re-structuring their work lives to stay at home. That would be a good thing – a little bit like

SNCC sending a handful of Ivy League white kids down to Mississippi to work beside black folks and get shot at by the KKK. That relatively small number of white kids said “Holy shit!” and ran back to their dorms and helped other white kids see the system for what it was, and act to change it – hence, “The Sixties.” Maybe if enough men – it won’t be many – come back from changing diapers and say, OK, things have to change, then maybe that will trigger the change. I know the priveleged classes can do wonderful things when they’re appropriately freaked.

However, in writing about my experience I don't want to water it down and deploy a lot of flowery language about discovering your feminine, nurturing side, blah, blah, blah. I’m not interested in making parenthood or staying at home attractive for men, or women, for that matter. This blog is not an advertisement for parenthood or for stay-at-home-dads. Parenthood is what it is; you are who you are; you'll make the best decision for you. Maybe I have to accept that I am an example, but I don’t blame any woman or man for making different decisions. I've decided to start this blog to publicly chronicle my efforts to be a decent father and husband, and do something that not many men have tried to do. Let this first message serve as a half-assed, anxious manifesto. Welcome to Daddy Dialectic!