Anne Lamott isn't the kind of writer whom I ordinarily like; I prefer gloomy European eggheads. But during the first few weeks of Liko’s life, Shelly and I took turns reading aloud Lamott's classic memoir Operating Instructions: A Journal of My Son’s First Year, which we found to be hilarious and helpful.

Since then I’ve taken to reading her columns in Salon.com and I’ve really started to like the woman. It’s worth noting that Lamott does seem to be a little bit of a high-maintenance loon, but her writing is so amusingly human and relentlessly honest that I (for one) am willing to take her as she comes.

On May 22 she published a column in Salon detailing an “ugly and insane” confrontation with her now-17-year-old son Sam. Rather than quoting, I’ll let you read it. Sufficed to say that the column is full of anguish and pain at her son’s bad attitude and the turn their relationship has taken in his teenage years, and pivots on a slap Lamott delivers in a moment of weakness. It’s a common story – I was Sam, once upon a time, maybe even a little bit worse – and Lamott tells her side as candidly as she can. She doesn’t make herself look good, either. That’s part of the point.

The column provoked (at this writing) nearly 400 comments from Salon readers, many of them sanctimonious (“it takes a lot of something -- hell knows what -- to slap another person in the face”), laughably misguided (“what would people be saying if he’d been the one who slapped her in the face?”), self-righteous (“you’re a beater”), and sometimes even misogynist (“someone really needs to take this cupcake out behind the shed and slap her around”). Other Salon readers ably rebutted the worst comments, so I won’t add to the chorus.

But here’s what most struck a nerve with me: many commentators also condemned Lamott for writing at all about her son. “Lamott… has made a habit of cannibalizing her son's life for profit,” writes one person. “Violating your son's privacy by sharing this story here is a bigger mistake,” writes another, “and one that I don't think I would have EVER forgiven my parents for had they ever written about my foolish adolescent misdeeds in a public forum read by millions of readers.”

Since starting Daddy Dialectic in March, I’ve received two emails from people who called the blog “exploitative” for writing about my experience taking care of Liko; my critics even seem to be under the impression that I write Daddy Dialectic for some kind of financial gain. To which I reply: Ha! You have no idea what you’re talking about.

And so my first instinct was to side with Lamott; the first draft of this blog entry consisted of a defense of Lamott’s right and even duty to write honestly about her experience as a single mom.

However, in the process I thought a great deal about the limits, real and potential, that I impose on what I share and don’t share in Daddy Dialectic. Liko is still a toddler and so there is nothing I can write here that will reverberate in his social and emotional life; he’s just a little guy with little-guy problems, like learning to sleep through the night. The point of the blog is to document my own responses as a primary caregiver and think politically about my experience, based on the assumption that a dad-at-home is still a relatively new social phenomenon and therefore worth writing about.

However, there is a gigantic no-fly zone in Daddy Dialectic: my wife Shelly, who seldom appears except in passing. The reason is simple: she doesn’t want me writing about her. She and I have never discussed this, but after 14 years together, I instinctively understand that Shelly doesn’t want me talking about her or our relationship in any depth with a bunch of strangers, or even with friends.

And so you’ll never read in Daddy Dialectic about an argument we just had and any of my petty dissatisfactions as a husband. If, God forbid, one of us slapped the other in a moment of rage, you, dear reader, will just never hear about it. And I think that as Liko grows older, you’re probably not going to hear about our most painful growing-up moments. (There are, incidentally, ways to write about parenting in the teenage years that are respectful and appropriately distant. See, for example, the Daddychip blog.)

In the end, I guess I have to agree with some of Lamott’s more thoughtful critics, that in writing about an altercation with her teenage son, she might have showed poor judgment.

But here’s the thing: anything I write about my relationships with my wife and son, or any member of my family, is between me and them. Reading about one isolated incident in the life of a family is not license for the reader to judge an entire person or entire relationship, the way Lamott’s critics have done. Lamott showed courage in writing so frankly about her experience, and that should be honored even as we politely question her judgment.

Writers who share and explore their experiences perform a socially necessary task that our society rewards in various ways, through pay and prestige. It’s hypocritical to read Lamott’s writing and derive meaning from it, and then turn around and criticize her for writing at all. Lamott might (we’re not in a position to know for sure) have damaged her son and her relationship with her son by writing about their life together, but it can be simultaneously true that the column is useful to us as readers. Certainly, as the father of a future teenager, I read it very carefully, as a warning. For that, Lamott has my respect and gratitude.

-------------------------

One last, different note. Like many of you, this morning I read details of the latest massacre in Iraq perpetrated by American troops: “The 24 Iraqi civilians slain on Nov. 19 included children and women who were trying to shield them, witnesses told a Washington Post correspondent in Haditha this week and U.S. investigators said in Washington. The girls killed inside Khafif's house were ages 14, 10, 5, 3 and 1, according to death certificates.”

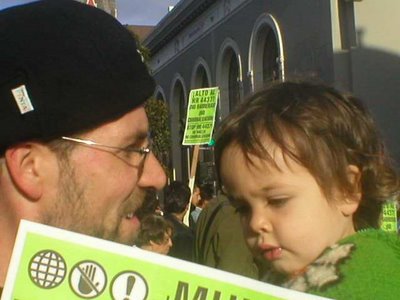

Imagine, right now, soldiers kicking down your door and murdering your children before your eyes. All of us as American taxpayers helped murder those girls; we paid for the guns. Wherever you are and whatever the circumstances of your life, do what you can to speak out against the war. It has to stop.