“Cyclops, Storm, Nightcrawler, Wolverine, Colossus. Children of the atom, students of Charles Xavier, MUTANTS – feared and hated by the world they have sworn to protect. These are the STRANGEST heroes of all!”

Image: Middle of the night. Jean Grey – the Dark Phoenix – returns home to Annandale-on-Hudson. She embraces her father.

Father: “This is fantastic! My goodness, girl, we haven’t heard from you in weeks! Why didn’t you write or call? Elaine! Sarah! Come Downstairs! Look who’s here!”

Dark Phoenix (thinking): “Oh, no! Please, no! My telepathic power is so sensitive, I can’t block out Dad’s thoughts. He’s an open book to me! Nothing’s secret, nothing’s sacred, anymore!

Mother: It's wonderful to see you, dear...You look thin, Jean. Are you eating enough?

Dark Phoenix (thinking): I can read Mom’s love for me, her concern. But beneath that – buried so deeply she probably isn’t even aware the feeling exists – she’s scared of me.”

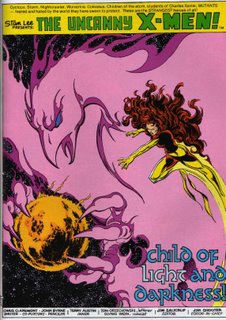

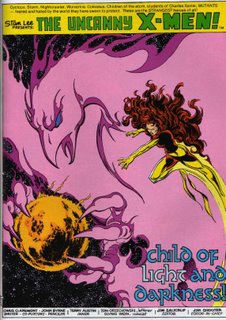

--from Uncanny X-Men No. 136: “Child of Light and Darkness”

Lately,

I've been thinking and writing a lot about comic books. I read comics from the ages of 11 to 14, when

I was a bookish social outcast in Saginaw, Michigan. When my family moved to Florida, I suddenly stopped reading them. (I also stopped running track, drawing, and playing the flute. In Florida I discovered punk rock, black clothes, and the joys of hanging out with other outcasts, and I didn't have time for much else.)

Years went by. I sold my comic book collection. I ended up in San Francisco. Along the walk between my house and my old office there was a comic book store, which I ignored until Liko was born. A month later, I found myself going in and browsing. The proprietor, a rotund black man with a beard like Karl Marx’s, watched me warily, like an unwanted houseguest. The new titles were displayed in the front of the store along a junkyard of racks; the rear was filled with paperbacks piled to the ceiling. During my first visit I tried to extricate one.

"Do you know how to put that back?" asked the proprietor, hands quivering, eyes almost fearful.

"Sure," I said. I started to put the title back in its stack but the proprietor snatched it from my hand.

"You’re not doing it right!" he shrieked.

For the rest of the day, I thought back on this encounter with a combination of bemusement and annoyance. Later, after I visited other stores in the Bay Area, I realized that this dude was a fairly typical example of a comic dealer - they all have the personalities of shut-ins and treat their disheveled shops like inviolable Fortresses of Solitude.

But I kept coming back. His distrust never wavered and I never saw another customer in the store. I found the titles of my pre-pubescence – Frank Miller's run on Daredevil, the classic Dark Phoenix saga, and the first 40 or so issues of the New Teen Titans, as well as random old favorites like Rom: The Space Knight and Jack Kirby's Kamandi: The Last Boy on Earth. I started to buy the omnibus paperbacks, one a week, in which many of these stories are collected.

Faintly embarrassed, I’d hide my acquisitions from Shelly, and in the dead of night I'd read them, sometimes with the newborn Liko cradled in the other arm. At 11 years old, the art had seemed fluid and beautiful to me, but as I re-read the stories, it took only the smallest effort to see through the action to how stiff and shallow the figures and backgrounds were. At times I giggled aloud at the ponderous solemnity of the dialogue, particularly in Chris Claremont's X-Men.

But I was transfixed by the stories. I've never been good at remembering my childhood; at times it seems to me that I slept, like an astronaut in suspended animation, through my first decade-and-a-half of life, only to wake at 14 or 15 on a strange alien planet called Florida. Reading the X-Men, however, I found that I remembered the stores in Saginaw where I’d gone to buy comic books.

The first was a convenience store that I could reach on my Huffy, where the comics had been displayed in a revolving rack near the entrance. I'd loiter there munching on

Twinkies and flipping through the pages; I don't ever remember the clerk telling me to get lost. I also bought comics at a specialty store called The Painted Pony, somewhere in downtown Saginaw. I remember the owner as a middle-aged, hunchbacked homunculus. He wore glasses that always sat at a tilt on his nose, whose lenses were so thick that they warped his eyes into ever-changing funhouse shapes. Was he really so grotesque, or are my memories distorted by childish perception?

One day after a trip to the Painted Pony, my dad asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up.

"I’d like to own a comic-book shop," I said.

My dad was silent as he drove through downtown.

"Are you sure?" he finally said. "Look at that guy in that funny-book store I take you to. [

My dad always called them "funny books."] Do you really want to end up like him?"

"What's wrong with him?" I wanted to know.

In general, my parents did not approve of my "funny book" habit. I think they saw comics as violent and emotionally unhealthy, and they were rightfully nervous about the social (anti-social?) milieu that surrounds the buying and selling of comics. But in reading the same comic books as a new father during the past two years, I've remembered many things about my comic-reading years that were previously lost to me. It's helped build a connection to my childhood that I think I need as a dad.

What really strikes me about these old stories, however, is how much, and what, they have to say about being a child and being a parent. Ninety percent of comic books are crap (

Sturgeon's Law: 90 percent of everything is crap), "but the remaining 10 percent is worth dying for." True enough. A series like the Dark Phoenix saga reads - I'm being completely serious - like a paradigmatic new myth about the inevitability of loss and the responsibilities that come with power. The parent-child relationship is at the center of the myth.

When Jean Grey discovers that her mother is secretly afraid of her - and parents, admit it: we're all a little bit afraid of our children - it's a terrifying moment for the child. "Behold your creation, Charles Xavier!" says Jean to her surrogate father, the leader of the X-Men, before she tries to kill him. Children represent the future, but they also evoke our mortality. In the end,

the entire X-Men series - which tells the story of the next stage in human evolution - is about accepting change, loss, and renewal. (Which, come to think of it, is probably why the Phoenix image has become so central to the series.)

Such were the lessons imprinted on my tender, confused little brain. During the past two years, I've broadened my reading and brought myself up to date in the state of comic book art. I've found that comics have matured and dramatically improved in terms of writing, art, and sophistication - in fact, most comics these days seem much more directed to adults instead of kids.

James Robinson's Starman series, which is thematically focused on the relationship between fathers and sons, was one of the first new titles I encountered. The last five issues of the 80-issue series are stunning, especially when viewed through the lens of Daddy Dialectic's themes. Jack Knight, who inherited his father's mantle as the superhero Starman, himself becomes a father. Jack's dad, the original Starman, dies, and so does the baby's mother.

Instead of retreating into superhero fantasy, Jack becomes a stay-at-home dad. "My son is more my life than...crime-fighting," says Jack. In the panels of the comic book, we see an exhausted Jack changing, feeding, and burping the baby, often in the dead of night, surrounded by laundry and dirty dishes. "My boy needs feeding. He needs changing. My boy needs love so he can begin to understand I'm his dad and not just some weird guy he got stuck with. He cries for his mom. He misses her. I cry too sometimes for my losses."

Later Jacks seeks the counsel of Superman. "I have a son," he tells the Man of Steel. "He needs me now. I don't want him to become an orphan. And... I don't know... something's gone. Some part of me. I'm not motivated like I was. Suddenly there's an unknown vista ahead and none of them involve crimefighting. Is that wrong?" He asks Superman's permission to quit. "You met evil with valor," Superman replies. "Now let others."

You have to understand: at the moment I read this, I was thinking of quitting full-time work and staying home with Liko. I can't say that I ever "met evil with valor," but I know exactly what Jack is talking about when he says, "I'm not motivated like I was." And it was incredibly moving to me to see such an accurate picture of parenting in a comic book: not a romanticized, fantastic picture, but gritty and real. In the end Jack does quit. He packs a station wagon and drives with his son to San Francisco, queer capital of the world.

Think about it, folks: this is a fucking

comic book that shows a man giving up his profession so that he can stay at home with his baby. Back in the Golden Age, Superman never would have done that. The superheroes of his time were muscle-bound warriors, not stay-at-home caregivers. In the end, giving it all up for his child is

the most heroic thing Jack can do. It seems fitting that a father-figure like Superman guides Jack in that direction; it feels like a watershed.

What if I had read that when I was 14? What if such images became commonplace in our culture?

Time's a funny thing. It seems like before we had kids, we were in this timeless bubble. We'd go out to plays and dances and clubs and bars whenever we wanted. We'd travel, we'd just hang out, we were a cool young couple going out on the town. There was a cafe/restaurant down the street from our apartment owned by an Iraqi guy who loved the fact that we were this young couple in love, and would give us cardamom-laced coffee on the house. Life was good, and it seemed like it would go on forever.

Time's a funny thing. It seems like before we had kids, we were in this timeless bubble. We'd go out to plays and dances and clubs and bars whenever we wanted. We'd travel, we'd just hang out, we were a cool young couple going out on the town. There was a cafe/restaurant down the street from our apartment owned by an Iraqi guy who loved the fact that we were this young couple in love, and would give us cardamom-laced coffee on the house. Life was good, and it seemed like it would go on forever.