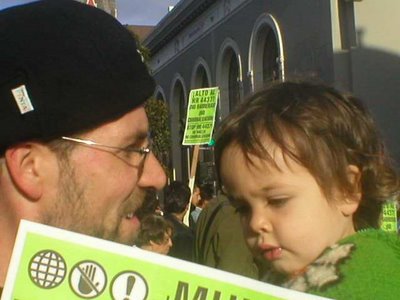

1. My grandmother – Nana, to me – died early Friday morning. That afternoon I took Liko to lunch. I found myself sharing with him my fragmented, half-submerged memories of Nana, though he did not, of course, understand me and spent most of the time throwing food on the floor.

The memories are not the sort of thing I'd write down. Nana didn’t share heartwarming stories by the fire. She didn’t play the piano beautifully or teach me to love Shakespeare. The most famous person she’d ever met was Jack Kerouac’s wife, with whom she’d go grocery shopping. She was a terrible cook. My memories of her do not stand out as instants in time, but rather as a Thanksgiving that did not begin and has never ended, one whose menu consists of dry turkey and cooked-to-death vegetables, with World Federation Wrestling and the Home Shopping Network playing endlessly in the background.

Yet she was humble and decent, the best sort of white, working-class New England Protestant. She had few illusions in life - as far as I know, she did not believe in God - and faced the end of her life with courage. I liked and respected her, and I’m going to miss her.

Liko met her once when he was only four months old. He will never know her or miss her. He will never know very much about her. This seems typical of my atomized family, whose mutually suspicious members are scattered across the continent.

2. All parents secretly long for the day when their children will be able to look past the unreasonable punishments and emotional failures and petty hypocrisies that infest all parent-child relationships, to finally see whom their parents really are and why they did all the things they did. We wait for our children to have children, so that we will be finally understood and forgiven.

But in my experience a parent’s desire for vindication is almost never fulfilled. Relationships with children are never de-complicated in the way a parent hopes, for the simple reason that life doesn’t work that way. Living systems grow more complex, not less; only death simplifies.

Well into maturity, the relationship with our parents keeps convoluting. We may respect our parents more and understand them better when we become parents, yet we still have to deal with their actual personalities.

In fact, seeing our parents more clearly through adult eyes can be much more painful than any disappointment we suffered as children or adolescents. The home a parent creates is all a young child can know; there’s no way for a child to measure her experience against another’s. The trust and thrall is absolute; our family is the one true family.

But children grow. They compare and contrast. They learn – they have to learn - to mistrust. Fissures and shortcomings appear. Families are like any institution, community, nation – some offer more freedom than others. Many of us come into young adulthood striving to be free of our families so that we can live the lives we have imagined.

The parent sees ingratitude, but the child is only protecting herself: I love you – what else can I do? – but you can’t tell me what to do and you can’t hurt me anymore.

3. I’ve found myself thinking recently about what a vast proposition and long journey parenthood is, and how there are so many opportunities for failure along the way. My teenage years were defined – I can admit this now that I am a father, I would have denied it then – by the long, slow disintegration of my immediate family. I don’t write this to embarrass my parents; it’s a common enough occurrence and there’s no shame in it. In fact, today the family divorce, that rite of passage, is worn like a red badge of honor.

Perhaps my parents were happy for all the years that came before, loving and cooperative, even as strains built up, repressed, perhaps, “for the sake of the children.” But today their marriage is defined in my mind by its ending, not its beginning or its middle. My parents have to live with the memories I have, unfair and half-seeing as they are. You can’t simply erase the past – or rather, you can’t erase other people’s memories of the past. You can’t replace their recollections and responses with a set you might find more congenial. You have to find a way to live with other people’s memories. You have to find a way to live with your own.

And so it goes. I can be the perfect father now and for many, many years to come – but what will happen when Liko is twelve? What kind of person will I be and what circumstances will we face? What kind of relationship will I have with my wife? Are there strains building within our little family that we are now repressing, sacrifices of selfhood made for the peace of the moment, that will ultimately undermine our collective happiness and integrity? How can we save ourselves, if indeed we need saving?

Liko will not remember his infancy or toddlerhood, when I changed countless diapers and wiped an infinite amount of snot and casually saved his life twelve times a day. Will I still be there for him when he is thirteen? Will I still take care of him at fourteen? Will he be as alone as I was? The uncertainty is maddening, and I feel an entropy, an accumulation of random errors, at the liminal edge of my experience that resists any conscious design on my part. The end is coming. The end is always coming. It never stops and no amount of love and sacrifice can stop it. We can only start again. Liko will never know his grandparents and he will always live far away from most of his scattered relatives, no matter where he lives.

4. From "How to write a memoir," by William Zinsser in the current issue of American Scholar: "One of the saddest sentences I know is 'I wish I had asked my mother about that.' Or my father. Or my grandmother. Or my grandfather. As every parent knows, our children are not as fascinated by our fascinating lives as we are. Only when they have children of their own - and feel the first twinges of their own advancing age - do they suddenly want to know more about their family heritage and all its accretions of anecdote and lore. 'What exactly were those stories my dad used to tell about coming to America?' 'Where exactly was that farm in the Midwest?'"

Some children grow up to be good friends of/with their parents. Few and far between, but possible.

ReplyDeleteI know. I actually consider myself to be friends with my parents, to the degree that's possible. And I really do respect them more.

ReplyDeleteMy simple and not very original point actually applies to nearly every long-term friendship that I know of: the deeper the history, the more complicated the relationship. Our relationships with our parents are the deepest of all.

When I think about my best friends, I find that our relationships contain at least one betrayal (S. dated my ex-girlfriend and didn't tell me; A. lied about where she was going; M. talked trash about me with Z.; and so on). If the relationship survives the betrayal, then in time it can deepen in interesting ways - your friends become more like siblings, and somehow less optional.

But it would be dishonest of me to deny that there is a deep pessimism at work in "Jeremy vs. Liko," which is of course shaped by the family background I allude to. When I write something like this, however, I don't assume that the worst will come to pass -- that, for example, I will abandon Liko at a time when he needs me most. Instead I am giving myself a warning: keep it together, Smith. Like Orwell writing 1984, I feel that by writing out my fears of the future, I can prevent the worst from coming to pass.

I'm also trying to work towards acceptance of my family as it really is -- that is to say, fragmented -- and understand how I build the family I want within the limits that we face.